The Comfort Board

A catalyst for conversation

The Comfort Board

A catalyst for conversation

Participatory policy design is increasingly being adopted by democratic governments around the world to ensure human voices are at the centre of policy design by engaging those most affected by policy in defining policy problems and identifying policy solutions.

"Policy design occurs far from the places where policy implementation happens. As such, it is removed from the gritty environments experienced daily by citizens and service managers as they translate policies into actions. Information relevant to policy design and the promotion of better outcomes does not automatically filter back to the policymakers in ways that can inform their design work."

As more and more policy issues are becoming increasingly complex, conversations associated with these issues become overtly technical and expert-led. Often the voices and views of affected communities can be marginalised or lost.

In 2016, Toi Āria developed and trialled a methodology, now called the Comfort Board, in response to a project which required an effective engagement with a cross-section of New Zealand people. The methodology aims to elicit the ‘lived experience’ of everyday people. It gathers from participants a range of attitudes and experiences to a particular issue or problem based on their own life experiences and enables everyday people to participate in participatory processes.

The Comfort Board offers participants an engaging process for deliberation and a catalyst for conversation.

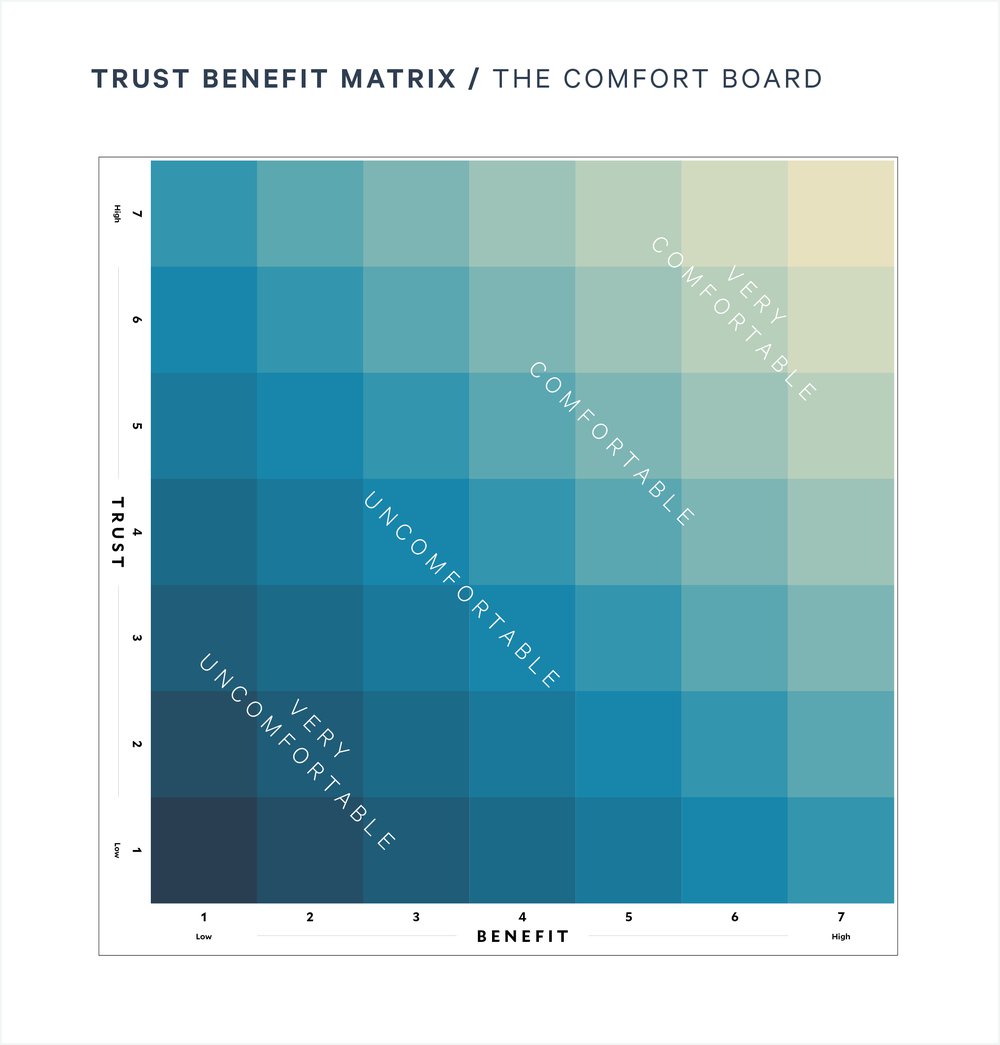

The Comfort Board process begins with participants gathered around the floorboard. The floorboard replaces the usual axes of a matrix that one might expect, such as ‘risk’ and ‘benefit’, with ‘trust’ and ‘benefit’ and a corresponding diagonal ‘comfort scale’. A facilitator reads out a scenario to them. This initial scenario is based on an easy to understand or familiar situation close to their lived experience and linked to the issue being explored. Participants are invited to think about their levels of trust and benefit in the scenario and stand on the board in the place that corresponds to their level of comfort.

One of the most significant insights from the Comfort Board's use to date is the way it can engage and appeal to a wide cross-section of audiences. In New Zealand, the groups most likely to be targeted and affected by policies in the social and economic domains are the very groups which the public sector has the most difficulty in reaching effectively, despite being the most important to connect with. In some cases, it is even legislated that such engagement occurs. In this context, it is crucial that policymakers are able to include the views of these communities in the design of policy solutions drawing on culturally appropriate methodologies.

In an early prototype of the Comfort Board approach, a Māori participant offered a useful critique of the language used in the facilitation. The framing of how to respond to the scenarios was, he felt, very pākehā focused (the dominant colonial narrative) in its singular first-person framing — in his words:

"I don’t see myself or my community in this."

This led to further iterations on how to frame the methodology for workshop participants and resulted in the following narrative for facilitators:

"A question we’re often asked is, should this be from my personal perspective, or should I consider things like my family, my community, or even the country’s perspective? Because viewpoints are different for different people according to their worldviews — you can weigh up and give your views on as many of these perspectives as you find relevant."

There is a continuing need for communities ‘most affected’ by decisions to be involved in the design and deliberation of the very guidelines and policies put in place to protect them. Engagement with marginalised communities must strive to replicate best practice, that based on an equal partnership, drawing on equal resources, in which appropriate cultural protocols and behaviours are acknowledged and adhered to, with expectations that genuine input might result in policy change.

Designers and policymakers need to ask those with lived experiences for their views and use their voice with care and respect.